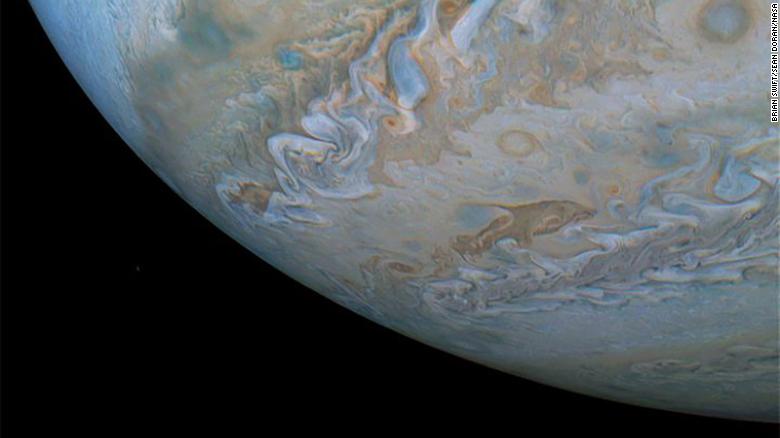

NASA discovered a black spot on Jupiter 2,200 miles long

Published: 17 December 2019, 11:03:58

Juno’s cameras spied giant cyclones gathered at Jupiter’s poles soon after its arrival in July 2016 — nine to the north, and six to the south. The central cyclone at the heart of the gathering was as big as the United States.

Five giant cyclones seemed to hold court at the south pole, keeping in tight, stable formation around a sixth central cyclone and not allowing other nearby cyclones to join their pentagon-like formation.

“It almost appeared like the polar cyclones were part of a private club that seemed to resist new members,” said Scott Bolton in a statement, Juno principal investigator from the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio.

But on November 3, Juno flew a daring 2,175 miles above Jupiter’s clouds and conducted its 22nd flyby since its arrival. This latest flyby revealed that a new, small cyclone had been allowed to join the exclusive group.

“Data from Juno’s Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper [JIRAM] instrument indicates we went from a pentagon of cyclones surrounding one at the center to a hexagonal arrangement,” said Alessandro Mura, a Juno co-investigator at the National Institute for Astrophysics in Rome. “This new addition is smaller in stature than its six more established cyclonic brothers: It’s about the size of Texas.”

Only time will tell if the small cyclone will grow to reach the size of its neighbors. It already has a similar sustained velocity of 225 miles per hour.

Cameras on Juno were able to take a deeper look at the atmospheric process happening on Jupiter and peek inside the weather layer 30 to 45 miles beneath the cloud tops. Combined, this data not only offers insight about Jupiter but also about other gas and ice giants in our solar system, as well as how the atmospheres of exoplanets may behave and even similar storms on Earth.

“These cyclones are new weather phenomena that have not been seen or predicted before,” said Cheng Li, a Juno scientist from the University of California, Berkeley. “Nature is revealing new physics regarding fluid motions and how giant planet atmospheres work. We are beginning to grasp it through observations and computer simulations. Future Juno flybys will help us further refine our understanding by revealing how the cyclones evolve over time.”

But detecting the cyclone was only possible because engineers helped the solar-powered spacecraft navigate an eclipse that could have ended the mission by freezing it out.

“Ever since the day we entered orbit around Jupiter, we made sure it remained bathed in sunlight 24/7,” said Steve Levin, Juno project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “Our navigators and engineers told us a day of reckoning was coming, when we would go into Jupiter’s shadow for about 12 hours. We knew that for such an extended period without power, our spacecraft would suffer a similar fate as the Opportunity rover, when the skies of Mars filled with dust and blocked the Sun’s rays from reaching its solar panels.”

Inside Jupiter’s shadow, Juno would face temperatures far colder than it was tested to withstand, which strains its batteries past the point of recovery. The mission team strategized a way for Juno to “jump the shadow,” according to NASA, to just miss the eclipse. A system burn helped it jump ahead and avoid the eclipse.

“The combination of creativity and analytical thinking has once again paid off big time for NASA,” said Bolton. “It was nothing less than a navigation stroke of genius. Lo and behold, first thing out of the gate on the other side, we make another fundamental discovery.”

Happily, Juno can continue to orbit and study Jupiter until the mission’s end in July 2021.